Klee in Wartime

This exhibition is the first to give a comprehensive view of the consequences of the First World War on Paul Klee’s work with reference to selected pictures from all phases of his career. In both artistic and biographical terms it was a time of profound upheavals. The war robbed Klee of many of his artist friends. Thrown back on his own devices, he continued to pursue his art. He commented on the political situation in his works and at the same time turned increasingly towards abstraction.

Our presentation of the collection picks up central aspects of Klee’s work which originate in the time of the First World War. But the content of the exhibition also includes Klee’s life as a soldier in the First World War. Klee’s rapid rise and his journey to become one of the central figures in modern art is also illuminated with letters and documents. Because in spite of its horrors, the time of the First World War was a very productive and extremely successful one for Klee. He enjoyed his artistic breakthrough in the middle of the war and became a cult figure for young artists between 1916 and 1918.

In the years leading up to the First World War there was a mood of elation in the air. Not least for Paul Klee, who was established in the Munich avant-garde as a member of the artist’s group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), and who had discovered Cubism in Paris. His trip to Tunisia in the spring of 1914 impelled him in the direction of abstraction. For Klee, the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914 seemed at first like a severe setback. His artistic milieu suddenly dissolved: many of his friends went to war or into exile. Klee remained behind on his own in Munich.

In March 1916, at the age of 36, Klee was conscripted as a soldier of the German Reich. He was spared the horror of the front, and spent most of his military service on military airfields, often behind a desk. That way he was able to advance his artistic work even during the war. The artist commented on his life as a soldier in his diary and in letters with startlingly ironic detachment. In spite of the terrible events of the war, the years from 1914 until 1918 proved to be a very fertile time for Klee. He discovered new materials, such as the cloth of aeroplane wings, and new tools such as the stencils with which he had to paint aeroplanes. He developed his work further in a formal sense, opened up new subjects and creative media and delved further into those he had already tried out. The exhibition looks at central aspects of his work which originate during this time, and pursues their development into later periods of his career.

Throughout those years – in the middle of the war – Klee experienced his artistic breakthrough, and between 1916 and 1918 he became a cult figure among young artists. During the last years of the war and the years that followed, his artistic successes were rewarded with numerous exhibitions, rising sales prices and publications. After the end of the war he was politically involved in the communist Munich Soviet Republic, which only lasted for a short time. Klee repeatedly portrayed himself as the dreamily remote, unworldly artist – as he is also perceived today. The exhibition shows a different side of Klee: as an eye witness who picked up political, cultural and social changes and reworked them in his art.

Comments on politics

Even if Klee would not describe himself as a political artist, from the outset he regularly produced works that referred to politics and society. In the titles of his creative commentaries on contemporary events Klee very rarely mentions specific individuals or events. Instead he uses types such as the proletarian, the general, the pub talker or the commander to caricature real politicians or comment on the political mood. The situation just before and during the First World War and the period of Hitler’s seizure of power in the early 1930s, which led to Klee’s flight to Bern, certainly made their mark on the artist. This is apparent in numerous works shown in this exhibition.

The discovery of Cubism in Paris

In April 1912 Klee travelled to Paris, where he met artists including Robert Delaunay in their studios. It was during his visit to Delaunay that Klee first encountered experiments involving the combination of colours and planes with no reference to figurative objects. In galleries he also discovered Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Following the model of Cubism, Klee learned how to depict the world from different perspectives at the same time. The result of these encounters was that from now on Klee abandoned perspectival representation in his works and stressed the two-dimensionality of the picture surface by giving it a vivid and rhythmical structure of colour fields.

The path towards abstraction in Tunisia

If we believe his own diary entries, it was only during the Tunisian trip that Klee finally mastered the “colour scale”: “Colour possesses me. I don’t have to pursue it. It will possess me always, I know it. That is the meaning of this happy hour: Colour and I are one. I am a painter.” However a look at some of the watercolours made before the trip already reveals convincing coloration. In the works from this time a development towards complete abstraction is already apparent: buildings and landscapes break down into colour fields. The impulses to abstraction that Klee received in Paris, whether in his treatment of colour or with colour fields, are confirmed and further plumbed in Tunisia.

Flight from reality

With abstract symbols such as the circle, the crescent, the star or the triangle Klee attempted to depict the terrible time of the First World War without depicting reality directly. Works like Destruction and Hope or Drawing for Unlucky Star of Ships refer directly to the menacing situation. In other works such as Hermitage Klee seems to turn away from the present, to find refuge in a fairy-tale world. He invents his own landscapes, in which nature, animals, plants and celestial bodies play the main part. The frequently used motif of the eye reinforces the impression of mystery in these works. But the fairy-tale watercolours cannot be seen simply as a renunciation of reality, but as products of Klee’s contradictory perception of the state of war. As early as 1915 Klee notes in his diary: “The more horrible this world (as today, for instance), the more abstract our art, whereas a happy world brings forth an art of the here and now.”

War, persecution and death

Klee repeatedly addressed the state of war in his works. But he was barely able to sell works like this from 1914 to 1915. This is probably one reason why Klee considered a more abstract pictorial language more appropriate to the expression of contemporary events. But alongside his crystalline Cubist works in colour, Klee managed to capture the mood and atmosphere just before and during the First but also the Second World War. The artist thus reveals a keen ability for capturing and depicting the menacing situation in which people were living.

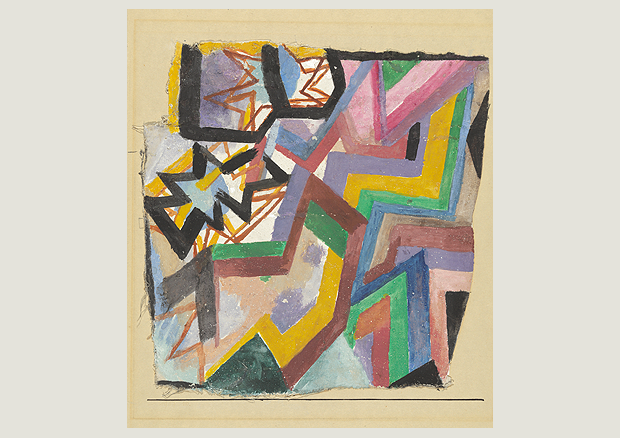

Explosive zigzag

In 1917 Klee produced a series of works with “angular zigzag movements”, as he later described them. The exploding lightningflashes are an expression of the oppression, fear, menace and destruction to which people were exposed at the time. They are also, however, abstract techniques that enable Klee to give visual form to energy and dynamism. These works impressively visualise how Klee manages to express experience with purely abstract devices such as line and colour.

Crashing down arrows

During his military deployment at airfields, Klee also had to record and photograph plane crashes by trainee pilots. Klee seems to have taken barely any interest in flying techniques. Instead he was fascinated by flying or gliding as such, and as a contrast with our earth-bound existence. From his experiences at the flying school he went on to produce a series of semi-abstract works with plunging aeroplanes and birds or a mixture of both in his plane-birds. The works often show arrows, partly as a memory of the aeroplane flechettes thrown from the planes, as in The Dart House. Soon they became a symbol of movement, power and energy as such. The arrow remains of central importance in Klee’s late work.

Numbers and letters

At the flying reinforcement division in Schleissheim, Klee’s responsibilities included the painting of aeroplane coverings. During this period he painted his first works on leftover scraps of aeroplane linen and using letter stencils, which led in the years that followed to further experiments with fabrics and letters. From January 1917 Klee worked as a clerk in the cash department of the flying school in Gersthofen. This book-keeping activity also left traces in his work – for example, he sometimes integrated columns of numbers into his compositions. Some works were produced on lined paper on which he performed his calculations, or on stained blotting paper.

Scenography fluchtpunkt.xyz